Bond 25, the next instalment of the 007 franchise, is employing a sustainability consultant on its shoot to ensure greener practices happens from the ground up, but there are steps all productions can take to reduce their carbon emissions.

Just one hour’s worth of TV content produces 13 tonnes of carbon dioxide - and drama is one of the biggest culprits, according to Bafta’s industry-backed sustainability project, Albert.

Albert’s annual sustainability report, which aims to get the industry thinking about its environmental impact, revealed that drama produces almost 45 tonnes of carbon dioxide per year compared to factual output’s 12 tonnes, entertainment’s 10 tonnes and sport’s 3 tonnes.

The flights, the kit, the size of the average crew and the one-off nature of many shoots (as opposed to the back-to-back filming of a long-running entertainment series in a TV studio) all contribute to drama’s larger footprint.

To counter this, high-profile productions such as Bond 25 are employing sustainability managers to ensure green measures are taken from the ground up. In TV meanwhile, carbon reporting is now mandatory for all the UK’s major terrestrial broadcasters.

And it’s only a matter of time before the pressure grows on productions and their suppliers to take visible measures to reduce their carbon emissions too.

The good news, according to Albert head of industry sustainability Aaron Matthews, is that this something that all dramas can work towards and the earlier they do so in the production process, the better.

“Our aim is to get crews discussing the entire carbon footprint of a production at pre-production stage in those regular head of department meetings, rather than focusing on single issues such as water bottles, because it’s those bigger conversations around lighting and production and catering that will make the biggest impact,” he says.

Matthews points out that plastic water bottles account for less than 1% of carbon emissions compared to props, which account for around 5% and air travel, which can contribute up to 40%.

“Rather than focusing on single issues such as water bottles it’s the bigger conversations around lighting and production and catering that will make the biggest impact.” Aaron Matthews, Albert

Energy choices

So, what can productions do to make a notable difference? One easy win, says Matthews, is to switch to a renewable energy source.

In 2017, Albert helped 25 companies move to renewable energy tariffs, with its group purchasing scheme initiative, Creative Energy, saving a total of 300 tonnes of CO2.

In the UK, participating companies include hire firm Procam, post house The Farm as well as indies such as Mammoth Screen and Baby Cow.

Matthews adds that the cost of electricity from a renewable energy company is broadly similar to ‘brown’ from fossil fuels.

“Some companies save, others must pay a premium based on how good their previous deal was. But typically, the difference is less than 5% in either direction,” he says.

Matthews adds that productions should also start asking their post houses and studios if they too are on renewable tariffs.

“They might not care if only one client asks this question but if 1,000 people are asking for the same thing they’re more likely to make the switch,” he says.

In terms of all the extra storage that new formats such as UHD and HDR require, Matthews recommends that producers also ask questions about where their data is being stored.

“Sustainability needs to happen at the beginning of the process, along with the budget and the vision; set your stall out, tell people that it matters and reiterate it at production meetings.” Howard Ella, Mammoth

Reducing the use of fuel-guzzling on-site generators during filming is another measure that can help reduce emissions. Mammoth Screen reduced its studio carbon emissions by 85% and emissions on location by 50% on the latest series of ITV drama series Victoria, by plugging into the National Grid and using house power.

According to Howard Ella, Albert champion and joint head of production at Mammoth, the increased studio power did lead to higher electricity bills, but when balanced against the cost of generators on the previous series, the switch delivered modest savings.

For other productions it’s not always possible to ditch generators, but there are greener alternatives.

Green Voltage is a company set up by Adam Baker and David Sinfield, a film gaffer whose credits include Aladdin and Wonder Woman, which offers the battery-powered, rechargeable generator, Voltstack.

It claims to be emission free, providing crews with easy access to clean, reliable power – which, due to an absence of diesel fuel - is also silent – making it useful in emissions-sensitive areas and noise-restrictive locations. “You can use it for a whole day’s worth of DIT (digital imaging technician) in a van in central London,” Baker adds.

Baker claims that the 2KW generator can save crews 25kg carbon while the 5KW units save 35kg when used over an eight-hour period. “Charge-taking from renewable source also maximises this impact,” he adds.

The generators have been used during the filming of Peter Rabbit 2, and for the upcoming US Netflix series Cursed and on a forthcoming theatrical version of Emma, which used a 2K Voltstack to maintain the DIT after shooting.

Lighting

Opting to use more energy-efficient light sources, such as fluorescent lamps or LED film lighting over tungsten or HMI (hydrargyrum medium-arc iodide) is also an increasing trend.

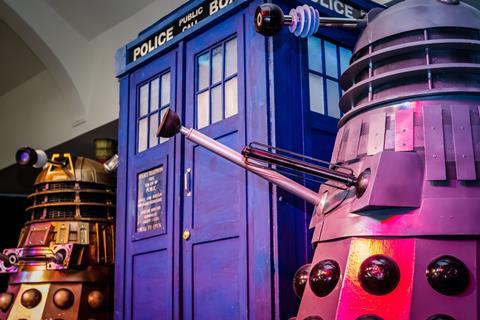

Even the Tardis now uses low energy lighting. In its Cardiff studios around 60% of the lighting on BBC sci fi series Doctor Who is now low energy, with fluorescent Kino Flo lamps replacing tungstens, compact fluorescent tubes replacing space lights and LED panels being employed more often.

Using lower power LED on set also allows the crew to plug into local power sources, rather than using generators - a practice employed by Red Planet on its recent BBC1 drama series, The Victim.

However, while LEDs are extremely efficient, they’re still limited in overall light output. According to Ella, sometimes it’s a matter of waiting for the technology to catch up.

“LED lighting can be achieved in a fix rig studio drama but if you are on location it’s hard because you tend to use 5KW and 12KW lights.”

“Large scale locations – such as inside a cathedral or a big house – take a huge element of lighting and in this case tungsten is still preferable - it would take an incredibly powerful LED version to replace it, and we’re not there yet,” he says.

However, according Jani Lehtinen CEO of Valofirma, a Finland- based full-service rental house that pledges sustainability as one of its core values, LED technology has taken “huge steps” in recent years.

He adds: “Getting exactly the right amount of light is cool but it also needs to be sustainable – LED can’t yet do all things you can do with HMI and tungsten, but it’s coming.”

Lehtinen, who has also worked as a gaffer on productions including Netflix’ Howards End and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, recently used LED lighting on a moonlight shoot for a Lapland-located commercial.

To achieve optimum results he advises DoPs and other HoDs to approach sustainability as they would like other production challenge on set.

“You need to allow yourself enough time to plan. The more time you have to concentrate on the image you’re lighting, the better.”

Props and costumes

Costumes, sets and props are the other notable area where drama crews can reduce carbon emissions.

On the set of The Victim the costume supervisor bought some of actress Kelly McDonald’s outfits on ebay, while Mammoth hires most of its period costumes.

Even costumes made from scratch can be made more sustainable by using the right materials. The Cybermen’s undersuits on Doctor Who, for example, are made of foam latex - the base of which is a naturally occurring biodegradable material - while the rest is polyurethane, which can be recycled as an energy source.

There are also schemes that productions use to help cut carbon and reduce waste such as Greenscreen, a joint initiative between Film London and environmental consultancy Greenshoot.

Participants have included the production team on Theory of Everything – which, through Greenshoot donated bundles of coats, jackets and blankets to London homeless charity The Upper Room.

In terms of sets, Ella advises art departments look at the materials they use: “How much timber is being used and where has it come from? How do you plan to reuse or dispose of it?”

For Poldark, sets from previous series were reused or hired while sets and clothes were donated to sustainable waste and reuse companies like Dresd and Scenery Salvage who are willing to dismantle and repurpose sets for less than it would cost to send to landfill.

A sustainable approach

While on set sustainability is often talked about as a cost saving exercise, Ella sees it more moral imperative than financial one. “If there are savings, they’re a bonus,” he adds.

Ella also doesn’t think that one type of drama – a location-based piece, say, is necessarily any more carbon intensive than a studio-based production.

He says: “It’s very hard to generalise where carbon emissions can be reduced.

“On (BBC drama) Noughts + Crosses we shot in South Africa, so a large amount of emissions came from the flights, but once we arrived the location team was really progressive in terms of putting sustainable processes in place…it’s more helpful to look at things on a project-by-project basis.”

Whatever type of drama you are shooting factoring, introducing sustainability into the process has to form part of basics of what the production team does on a shoot, Ella concludes.

“It needs to happen at the beginning of the process, along with the budget and the vision,” he says. “Set your stall out - tell people that it matters, reiterating it at production meetings and, as production moves forward, with crews. People generally buy into it, everyone understands that it is an issue.”

No comments yet