In its heyday, Quantel’s tools were the must-have items for finishing houses. In the second of IBC365’s Industry Innovator series, Adrian Pennington looks at how Quantel gave broadcast a quantum leap into the digital era.

Given the march of technology, breakthroughs are inevitable sooner or later but it’s the sooner part of the equation that can propel certain inventors and companies ahead of the pack. Some can even shift entire industries forward.

Such was the case at Quantel, the British brand which gave broadcast a quantum leap into the era of digital creative technology.

During the 1980s and 1990s, Quantel was in its heyday, riding high on the nascent postproduction industry it helped catalyse. Tools like Harry and Henry were must-have items for broadcast graphics and finishing houses on both sides of the Atlantic, with facilities trading on their ownership of one.

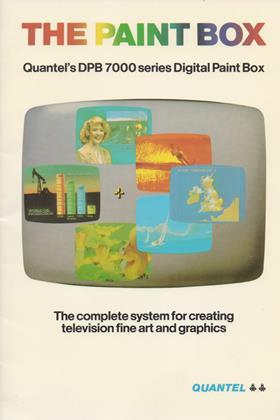

It arguably kickstarted the CGI revolution in 1986 when Paintbox, its best-loved machine, was used by director Steve Barron to make the video for Dire Straits Money For Nothing.

David Hockney, no less, enthused over Paintbox’s possibilities for “drawing with light on glass” in a richness of colour “that not even paint can give”.

Codebreakers

Paul Kellar, Quantel’s research director, likens the firm’s formation to the code breakers of the Enigma machine during World War II.

“Both were capable of lateral thinking, using imagination to find new ways of doing things,” Kellar tells IBC365. “Both were also a disparate collection of people. A coming together of minds. Richard Taylor was a fabulous engineer and leader. Others, like myself, had no management or leadership skills but were quite good at dreaming stuff up.”

Quantel was formed in 1973 by Anthony Stalley and John Coffey with the backing of Micro Consultants, a Newbury-based signal processing manufacturer set up a few years earlier by Peter Michael (knighted in 1989) and Bob Graves.

Originally to be known as Digit-Tel; the name was rejected by Companies House as being too close to US firm DEC necessitating a rethink. Peter Owen, who was its first employee, recalls that ‘Quantel’ was coined by his wife Rhiannon over breakfast “during an attempt at explaining the nature of quantised television signals.”

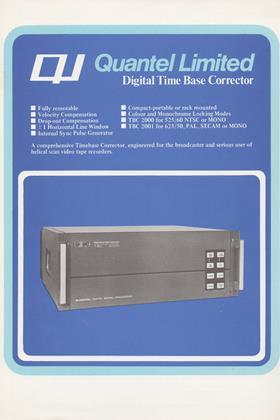

Its first products were digital time base correctors sold under the IVC (International Video Corporation) name in the US to compete with the then dominant Ampex Corporation.

When Coffey and Stalley left in 1975 to launch two new companies, Questech and GML, Quantel became the responsibility of Richard Taylor as managing director, and Paul Kellar as head of research, with Peter Michael as chair.

Taylor’s background was in cognitive systems and image analysis; Kellar was a Cambridge educated electrical scientist who had previously worked for Rolls Royce.

“From the beginning, the sales emphasis was to be on export,” says Owen. “This policy avoided the influence of and over-dependence on the BBC and ITV in the UK.”

1976 was a year of unprecedented export opportunity in North America; Montreal hosted the Olympics whilst the US faced presidential elections and celebrated the bicentennial anniversary of the day of Independence - all major television events, stimulating equipment purchases including new technology such as framestore synchronisers.

“Broadcasters were screaming out for some way of improving coverage,” Owen says. “We had to make a technology leap from time-based correctors to framestores.”

Luckily Quantel had one up its sleeve. Kellar had devised Intellect, the first framestore-based image analysis system which could accept and display live video, while at the same time allowing fast random access from a read/write computer port, a feature which was to become a key technology for future Quantel products.

“Once you have random access you can do anything with it,” Owen says. “You had the ability to make a quarter picture in picture and put a cool border on a live signal.”

Kellar and Taylor combined the Intellect with video interface mechanisms to build the DFS 3000 Framestore Synchroniser used by the Olympics broadcaster in 1976 to showcase a PiP inset of the flaming torch while the rest of the picture featured runners entering the stadium.

“Having made the leap to picture manipulation we knew there was potential in creative uses of technology,” Owen says.

At a time when this capability was regarded as requiring a mega-machine and huge rack space, Quantel’s manufacture of a complete framestore system in only 8.75 inches was both a bold step and important engineering advance.

“Because we found a way to make a framestore that was smaller and cheaper we could use several,” Kellar says.

The idea of having more than one framestore in a machine was considered “ludicrous” but the company’s next development relied on multiples of them.

- Read more: Industry Innovators: Bill Warner, Avid

IBC 1976 Paintbox prototype

Taylor identified the challenge of creating a system which would paint a line ‘as if a camera had looked at a real painted line’. The solution was to blend a bell-shaped brush of colour with the existing underlying image, a digital printing process that was repeated rapidly, overlapping previous stamps, as the brush was moved by the artist.

Quantel’s first public demonstration of digital painting, on a blank screen and onto stored images, took place at IBC 1976. R&D work continued to improve the quality based around a fundamental architecture which included pressure-controlled painting and multiple framestores for creating graphics in a way which did not destroy the original image.

It was the refinement of a pressure-sensitive pen which proved the killer app.

This innovation, disruptive at a time of keyboard ubiquity, effectively put Paintbox into the hands of artists and graphic designers. When it debuted in 1981 it benefitted from a menu and palette system designed by illustrator Martin Holbrook which was so intuitive it was able to be understood by non-technicians.

“The technology always aimed for realtime,” Owen says. “With that speed and with those tools it suddenly opened up the possibilities for creatives and broadcasters.”

Sales were made via broadcaster design departments, not engineering departments.

“It was about taking hardware for granted in a way that an artist could use and love it,” Kellar says. “We didn’t spend a lot on marketing in those days. We didn’t need to.”

Paintbox was expensive. “People quipped they could buy a lot of pencils for 70,000 dollars,” says Kellar. “It was good enough, useful enough - and we sold hundreds of them.”

Quantel’s next generation of live effects machine, known as Mirage, solved the problem of manipulating a live 2D television image into a 2D representation of a real 3D shape (the now-familiar ‘page-turn’ was created for the first time on this machine).

Taking advantage of the latest disc drive developments, it found that they could gang four parallel transfer drives of 470MB each to store 75 secs of 4:2:2 video and that with time code control of a D1 VTR it could be used for longer from editing.

The first commercial incarnation of this idea was launched in 1985 as ‘Harry’. This product fundamentally changed the post industry by bringing the tools of graphics, compositing, image resizing and editing to a pen and tablet workstation.

The concept was evolved with Henry the vision for which was expressed internally as ‘Harry with a sense of history’. Kellar says, “As long as any previous operation could be changed without starting again, then a serial processing engine could give unlimited flexibility. Effects, Paintbox and all the other processes could be included without having to build everything as a separate engine. New processes could even be added during the life of the machine.”

Henry’s ten-year life in the market place was proof of how advanced this concept was.

“It was exciting because the company was growing but when you have growth, it has to be managed all the way from R&D to manufacturing,” Owen recalls. “We were shipping and exporting a huge amount of kit which needed huge investment in automated assembly lines and pick and place machine which were pioneering at the time.”

This was a time of almost fabled extravagance when tools for post dominated headlines at tech trade shows. Digital telecine machines, for example, cost the best part of a million dollars.

“We had something special,” Owen says. “It was a very flat company in a way – everybody knew everybody else on first name terms. It meant that everyone from UI design to engineering to sales felt able to give each other feedback.”

It couldn’t last of course. Owen left in 2000, taking up a senior role within IBC. Kellar resigned in 2006 and has devoted much of his time since with teams at Bletchley Park helping to reconstruct an operational replica of the famous code-breaking machine Turing Welchman Bombe. Taylor sadly died in 2009.

Today, Quantel has almost ceased as a brand having merged with Snell to form Snell Advanced Media, subsequently acquired by the Belden Group and currently for sale as part of Belden’s divestiture of another stalwart brand, Grass Valley.

- Read more: Tim Shoulders on Grass Valley’s future

Kellar traces the seeds of decline to the firing of Taylor in 2005 by LDC, the venture capitalist group which took control of the company in 2000.

“They took the view that that company was too dependent on him. Their solution was to fire him. From then on the company was doomed.”

He adds, “We knew perfectly well that sooner or later machines would get cheaper and more software-based but there’s no question that, at that time, Quantel products needed purpose-built hardware. Making the transition to the desktop was not easy and one that has taken the industry more than 15 years [from 2000] to actually deliver.”

Quantel was ahead of the game. Its legacy lies in multiple patents (Kellar alone holds 33 and was recently granted Honorary Membership by SMPTE). The company was lauded with numerous Queen’s awards in recognition of export and innovation and it claimed eight Technical Emmies including for Dylan, a proprietary disc technology named after a character in The Magic Roundabout.

“We were the first to bring tools to graphics and illustrators which in turn opened up compositing for video,” says Owen. “We opened it up to those who were the least interested in what was in the machine bay. It was creative technology.”

2 Readers' comments