Esports is pioneering workflows that could be picked up by mainstream sports coverage, and with rising interest and growing prize pots, the influence of esports looks set to increase.

On August 25, the professional Dota 2 esports team, OG, caused a major upset by winning the richest esports tournament to date, The International 2018. Held at the 20,000 seat Rogers Arena in Vancouver, the $25 million tournament was witnessed by a capacity crowd over its six-day run and live-streamed by a peak audience of close to 15 million people.

In many respects, despite a total airtime of 122 hours, an esports tournament workflow for an event such as T18 looks very similar to a conventional sporting event, as the graphic below from Newtek shows. The only real difference lies in swapping the cameras and audio that would normally be capturing physical sporting action for gameplay capture, with production cameras being deployed essentially for cutaways, commentary and reaction shots.

With little or no heritage of using legacy broadcast circuits, IP-based workflows are increasingly dominant in the esports field as is remote production, which is becoming commonplace even at an intercontinental level. Coupled with the growing use of cloud-based tools, there’s a sense that esports is pushing workflows that will become mainstream in regular sports coverage not too far down the line.

This can inevitably entail the use of serious amounts of bandwidth and fewer and fewer productions are happy to be using the public internet, preferring to rent large pipes for their exclusive use.

As a case in point, The Switch supplied the 12th BlizzCon last month with 800Mbps of connectivity between California’s Anaheim Convention Centre to AWS, not to mention a 50Mbps link for ESPN to handle content for Twitter.

Private networks also minimise the problem of latency. Aside from the desire to attract audiences — and BlizzCon, for example had 40,000 attendees — one of the main reasons that tournaments take place in arena settings rather than having players log in from home is to provide an even playing ground when it comes to connectivity. Lowest costs circuits are not always the best nor the most direct route, a factor which contributed to League of Legends developer Riot Games building its own dedicated backbone, Riot Direct.

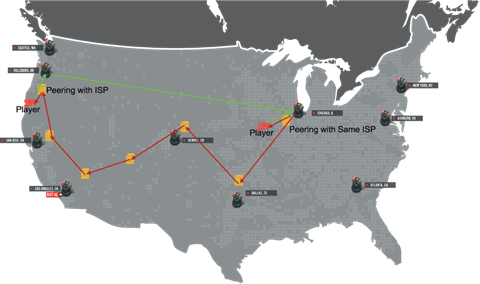

This is a move more commonly associated with major tech companies such as Google and Facebook, but provides a much more direct route. The diagram below shows the impact when the return path, marked here in red, from Chicago to a player in Portland was computed by the standard Border Gateway Protocol.

Solo streamer

Esports is, however, about more than the tournaments, with influencer-based social video a key component on platforms such as the Amazon-owned Twitch, the Microsoft-owned Mixer, Smashcast, Caffeine, and an increasing number of other outlets.

Monetised by a combination of adverts and subscriptions, some of the players are becoming genre stars in their own right, led by the Fortnite-playing Ninja, who currently has over 12 million followers.

The tech behind connecting player to audience tends to be the standard value-end of broadcast kit list as developed and refined on YouTube over the years, with added computing grunt and specialist live-streaming and video mixing apps such as player.me, XSplit or OBS to allow broadcasters to intercut the gameplay. Additional specialist broadcasting software such as StreamLabs, StreamElements, Muxy and OperaEvent provide an impressive and constantly evolving array of engagement and monetisation tools.

Over 200 third-party extensions are now available for Twitch alone, which generate customisable onscreen info about everything from player stats to avatars to viewer polls, provide tipjar functionality, enable charity donations, viewer-chat and a whole lot more.

Sports crossover

Viewer chat and the live, interactive and communal nature of game streaming is considered by many to be one of esports’ killer apps and live viewing is very much where the action is. Data from the most recent Nielsen Esports Fan Insight survey suggests that in the past 12 months 72% watched a live streaming event online, dropping to 48% for a pre-recorded match.

So far, so normal sports, but one of the dangers of mapping traditional sports paradigms onto esports is that it is a very different mindset.

“Monetisation remains problematic when measured against an established culture of free content”

According to Nielsen data, esports fans are, in general, video game fans first and foremost. They may spend on average 8% of their media time consuming esports, but they spend nearly a quarter of their time playing video games themselves.

The reason they watch esports is primarily to become better players themselves; they are active participants in the same games in a way that traditional sports organisations trying to build grassroots fanbases can only dream about.

This has implications. First, despite the draw of live events, there is a huge audience for VOD highlights and replays. Add in that factor and YouTube actually overtakes Twitch as the most popular source of esports programming, at least in the US market. It means there is distinct demand for clips and highlights, and a real opportunity for analysis and annotation.

Second, it will necessarily impact on the way that the increasing amount of esports athlete data being captured is presented. Traditional sports player stats such as metres run or tackles made, serve to highlight the difference between the elite athletes and the watching viewer. But given the different levels of engagement with esports, the sense is that data should be presented more as aspirational: you can do this too if you practice hard enough.

As an example of the sort of metrics that are starting to feed into the game, Turner Sports has started to use eye-tracking technology to track individual player’s focus of intent during games which are then analysed post-match. The broadcaster is also adding the sort of sports science analysis that has become a staple of traditional sports in recent years, measuring factors such as response times and the visual acuity of the players.

Monetisation, ads, and evolution

One interesting current trend in esports broadcasting is the demand of the narrative, which is stemming less from a traditional sports model and more from a sports entertainment perspective. This demands both additional resource on behalf of the streaming services for capturing content specific to it, as well as more input at the tournament planning stage to ensure the ‘right’ personalities end up pitted against each other. Whether this will become the dominant format becoming further emphasised moving forward or whether esports will default to what can be considered a more purist, skills-first model will depend on the audience sizes achieved.

As will monetisation. As with much of the online media space, monetisation remains problematic when measured against an established culture of free content. Nielsen data suggests that as many as 1 in 3 esports viewers would refuse to pay anything to watch any esports content, though that has to be contrasted against culture that is happy to crowd-fund the huge purse on offer at T18, for instance.

Happily for continuing to fund the expansion in esports, a similar figure suggested they would pay for ad-free video. This might be tested sooner rather than later though. Amazon-owned Twitch drew criticism for ending ad-free viewing on Twitch Prime (essentially a suite of benefits for Amazon Prime subscribers) in September, directing those who wanted an ad free experience to the $8.99 monthly Twitch Turbo service.

Measuring the impact of that will be instructive, though, of course, apart from revealing that over a million people are watching at any given moment, like its owner Twitch tends to keep its viewing figures to itself. It continues to innovate to stay ahead of a surging market though, for example announcing the forthcoming karaoke-style interactive Twitch Sings that allows viewers to request songs through chat only last month.

Speaking at the October TwitchCon 2018, Twitch CEO, Emmett Shear, said: “I think we’re still at very early days on Twitch. It still feels like the start of the streaming world.”

And with esports revenues predicted to hit $905 million or more this year and still rising, the real tournament is only just starting.

- Read more MTGx calls for brands to play esports

- Read more IBC showcases esports

No comments yet