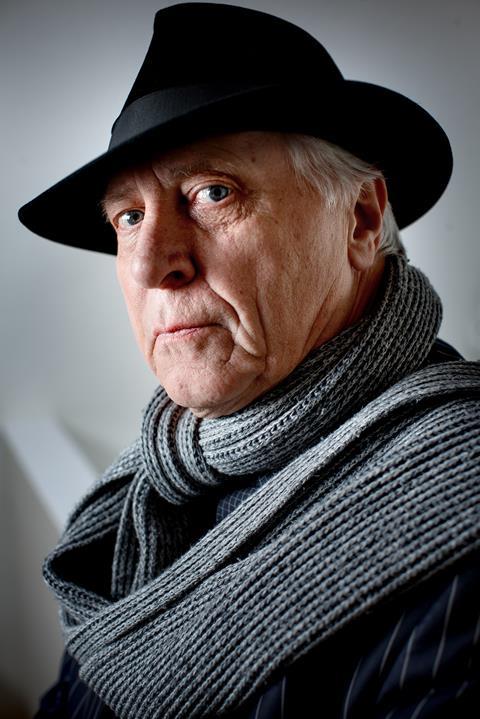

Cinema should evolve beyond the medium of storytelling. Speaking to IBC365, Peter Greenaway – filmmaker, artist and provocateur - casts his critical eye over Hollywood

Peter Greenaway would hate to be classified and indexed like one of the subjects of his films A Zed and Two Noughts and Drowning by Numbers. The maverick filmmaker, who became synonymous with British arthouse cinema in the 1980s, would prefer to be recognised for his own uncompromising evolution as painter, director, curator, art historian, theorist, video installation artist – even as VJ.

Above all, he relishes being a provocateur.

Greenaway’s anti-Hollywood sentiments are well documented and designed to court controversy. His main attack is that all film and TV is reliant on the medium of text rather than forging a genuinely independent and visually inspired language.

Calling for all scriptwriters to be given the sack - or shot, as he said in one interview - is mischievous shorthand for his belief that cinema is selling itself short by being rooted in storytelling.

When challenged that his distaste for cinema actually stems out of love for its possibilities, Greenaway agrees.

“That’s an accurate description of basically how I feel having played with cinema for about 40 years,” he tells IBC365.

“Despite the evidence, cinema is not very visual and is really a literary medium,” he contends. “Nobody seems to make anything without writing a script. Most cinema is some form of illuminated text. I would argue that we’ve yet to see any piece of cinema worthy of the name.”

The 77-year old is impatient for cinema to fulfil its promise as a breakthrough media for human expression, finding it stuck in the same formula throughout its short history.

“We’ve had 8000 years of lyric poetry, 5000 years of theatre, 400 years of the novel. Text has played so many games. Perhaps I am being unfair since cinema is still infant but does anyone need multi-screen adaptations of Jane Austen?”

Conservative format

Long before Martin Scorsese and Francis Coppola scorned Marvel movies as anti-cinema, Greenaway was condemning Harry Potter and The Lord of the Rings as cynical money-making exercises.

He feels the similarity between their argument and his to be superficial, instead chastising these cinematic legends for being part of the problem.

“Scorsese makes the same films as DW Griffith in f1910,” Greenaway says. “His films are structured the same way and are presented, organised and formatted the same way. He is working in very much a conservative format.”

I ask if he has ever been emotionally moved by a film but he ignores this. It doesn’t matter since, in his view, cinema needs to be ripped from its comfort zones of story and form whether that film is Casablanca or Apocalypse Now. He even invokes the Bible to make his case.

“In Genesis, it says ‘In the beginning was the word’. Not true,” Greenaway declares. “In the beginning was the image because how can He send anything out without an image?”

He continues: “If you believe cinema was born in 1895 [when the Lumiere brothers patented a movie camera and projector] then you’ll know that in the same year HG Wells, Johann Strauss and Van Gogh were alive.”

In contrast to the huge changes in artform since then “in literature (post-Borges), music (post-Stockhausen) and painting (post-impressionism),” he contends that the dial on cinema has barely budged.

“Other art forms have traded in old rituals… but cinema is intent on recording narrative”

“Other art forms have traded in old rituals and come up with so many extraordinary things but cinema is intent on recording narrative,” he insists. “There are very few filmmakers who have a great and profound sense of visual literacy.”

I counter that cinema language has evolved further than he gives it credit for and that there are cinematographers pushing the art of working in light, form and colour. Greenaway asks me to name some and I suggest Vittorio Storaro (The Conformist) and Roger Deakins (No Country for Old Men).

“Cinema has always worked with light,” he dismisses. “Charlie Chaplin worked with light. No-one is taking responsibility for cinema as a form of visual intelligence.”

He continues: “As much as I admire Deakins - his cinematography on Blade Runner 2049 is to be respected - I don’t regard that as a film and Deakins, like everyone, works to a script.”

With some irony then, Greenaway is accepting the Lifetime Achievement Award for Directing given by Polish cinematography festival Camerimage later this month.

He reserves a special place for Sergei Eisenstein, the Russian filmmaker who shaped the language of film editing, and The Last Year at Marienbad, a 1961 film by French director Alain Resnais which perhaps comes closest to Greenaway’s own experiments with heavily stylised non-linear form.

“Eisenstein was a shining light and one of the very few really cinematic film directors,” says Greenaway, who made biographical drama Eisenstein in Guanajuato in 2015.

Documentary films and attempts at realism get short shrift too. “What’s wrong with the notion of experiencing the world for what it is rather than fixing it in time? Do you want artforms to be about reality when the human imagination is the most extraordinary apparatus?

“I’m not against literature. I’m not against narrative,” he insists. His favourite book is The Bridge of San Luis Rey, a 1927 novel by American author Thornton Wilder. “I just don’t think they belong in cinema.”

He is fascinated by the form rather than the meaning of text, having made calligraphy central to his 1996 feature The Pillow Book.

It is painting, though, which he prides as the highest non-narrative artform – albeit one that cinema can yet emulate and surpass.

- Read more: Who is the greatest cinematographer ever?

“I am an archivist”

“I suppose it all began a long time ago in adolescence when I was first conscious of the ephemerality of everything,” the Welsh-born polymath explains. “There is nothing in my background or family or education related to painting but it occurred to me that drawing and painting was an attempt to somehow fix the ephemeral, to make it permanent. It is an archival pursuit. I could be described as an archivist.”

After art school in London he “tried and failed to make some sort of living as a painter,” then turned to the art of the moving image.

“I started writing articles as a journalist about the connection between the 450,000-year history of painting and the 120-year history of cinema,” he says, concluding that cinema was “desperately lacking in experimentation and needed a radical rethink of its theories and practice.”

It is the attempt to shoulder this responsibility himself which has been Greenaway’s lifelong project.

“Cinema can fuck with everything and is part and parcel of other art forms but I have always felt that it is lacking,” he says. “I am trying to invent a cinema which is present-tense, multi-screen and non-narrative. People find it difficult to imagine that. Maybe my demands are too high.”

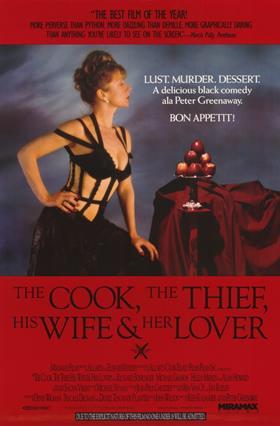

He gave “incredibly simple and rudimentary” storylines as a concession to audiences in his most well-known works The Draughtman’s Contract (1982), The Belly of an Architect (1987) and The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (1989) but it is the scientific organisation of these films which is striking. He uses taxonomy, maps, grids, numbers, diagrams, symbols, quotations and codes to break what he would describe as cinema’s formal rules.

Acclaimed for their visual acuity, his films are often derided as pretentious, fixated banally on themes of sex and death, ironically called out for their formalism and judged cold and devoid of humanity.

This would miss the mark of his coruscating sense of Thatcher-era politics in ‘The Cook, The Thief’ or the wit on display, notably in The Draughtman’s Contract.

There are elements of the cinema that Greenaway says he does appreciate. These include the use of sound (and silence), an experience of colour and performance, “a certain choreography” and, in particular, how all of these are “interwoven, connected, contradicted.”

“Cinema is a mechanical art. All digital technologies… are still a retinal phenomena that doesn’t fundamentally change the syntax and vocabulary of cinema.”

More recently he has embraced technology as a way of breaking the theatrical frame and says the film industry ought to have settled on 60 frames a second as a more ideal speed than 24fps.

“Cinema is a mechanical art,” he says. “Theatre technology is constantly changing. Like James Cameron playing with 3D. All these digital technologies I enjoy and have used, but they are still a retinal phenomena that doesn’t fundamentally change the syntax and vocabulary of cinema. They’ve been used for certain profit and entertainment but not metamorphosed cinema in any new direction.”

Multimedia art

His first major multi-media work was 2003’s The Tulse Luper Suitcases which spread across three films, a website, two books, DVDs and a touring exhibition.

His partnership with Dutch artist Saskia Boddeke has yielded several operas and music theatre performances with Greenaway writing librettos. Their latest multimedia installation, Artuum Mobile, features his sculptures and paintings

“I’ve never stopped painting or working on installations,” he says. “I’m still making films and still playing with museum-ology, the notions of gallery and replication.”

Greenaway has previously stated his desire to euthanize when he reaches 80 – just three years away. It’s one reason why he lives in Amsterdam.

“That was an intellectual argument,” he dismisses. “But can you tell me who did anything valuable after the age of seventy? Darwin, Einstein, Picasso had all done their best work by the time they were fifty. After fifty we are all fiddling in the dark or repeating what we’ve done before. My best ideas were 30 and 40 years ago and I’m still trudging through them.”

He suggests, with characteristic impishness, that old people only exist beyond the age of 80 “out of a sense of selfishness”, unable to contribute, using up valuable resources.

So, what does motivate him? “Curiosity,” he says. “And closing the gap between desire and practice in every part of life.”

Mostly he means bridging his conceptualisation of a purer cinematic expression with the ambition of achieving it.

“I am looking for a retina cinema in the sky.”

No comments yet