IBC365 takes an in-depth look at an increasingly popular choice for acquisition, with new methods trading cumbersome, data heavy workflows for virtually identical image fidelity but at lower data rates and file sizes.

Choice of camera and shooting format are intricately linked to post production, but getting from A to B with the best possible picture is fraught with decisions and trade-offs.

“In general, no matter what you choose, you will take a hit,” says Avid’s director of provideo marketing Matt Feury. “There is no best way, just the best way for your particular project. Do you have more time than storage? More money than time? The key is production agility. Depending on the type of programme there will be discussions between production and post regarding camera/codec options and their impact on storage/costs.”

All compression algorithms work to make files smaller while retaining resolution, colours and dynamic range to the best of its ability. An increasingly popular option for cinematographers, and one becoming available on a wider variety of cameras, is to record the Raw camera sensor data.

Sometimes referred to as ‘digital negatives’, Raw image files carry a far wider dynamic range and colour tonality from which to construct an image in post.

Lightly if processed at all, Raw files don’t bake in parameters like white balance and the images tend to be in native pixel count. The result provides greater flexibility for the creative process.

Proprietary codecs designed to get the most out of a camera manufacturer’s particular imaging sensor include ARRIRAW, Redcode Raw and Canon Cinema Raw. Sony offers 16-bit Raw out of its flagship cine camera Venice. Both the Panasonic VariCam line-up and EVA1 can output Raw data to external recorders.

Red cameras use the proprietary Redcode format which can be selected at recording ratios that range from 3:1 to 18:1. The closer the ratio gets to 1:1, the lower the compression, the higher the quality of the image but the higher the data rate.

While some cameras can only record one format (the ARRI Alexa 65 only captures ARRIRAW) most models offer several different flavours for recording video.

“Choice of codec and data rate will play the biggest hand in dictating quality,” Jai Cave, Envy

Choice of codec

The most popular two for broadcast TV acquisition are the H.264-based Apple ProRes, offered in flavours such as 444 XQ, 444, 422 HQ; and AVC with variants such as XAVC used by Sony, XF-AVC used by Canon or AVC-Ultra in the case of Panasonic’s cine camera range. For Panasonic users wanting to work in 4K resolution AVC-Intra Class 4:4:4 is offered on the VariCam, while on the EVA1 there’s AVC-Intra Class 4:2:2. Another codec, Adobe Cinema DNG, is available in several cameras including Blackmagic Design’s URSA Mini Pro.

“Choice of codec and data rate will play the biggest hand in dictating quality,” says Jai Cave, head of operations at Soho facility Envy.

For example, footage shot at 50Mbps data rate using an MPEG2 codec (HD422) is the minimum acceptable for UK broadcast. High end drama destined for Netflix, Amazon or for domestic broadcasters like Sky will require a higher spec, usually delivered at 4K and increasingly with an HDR grade.

That tends to require the best colour and dynamic range you can generate out of the sensor which is why Raw is an attractive option.

“The benefit of working with Raw is that you’ve got full control of what can be extracted from the original file,” explains Francisco Lima, visual effects technology supervisor, Gramercy Park Studios. “You are reassured that there’s not been any extra processing that could degrade the footage and cause issues when grading and performing VFX.”

If the project requires minimal colour-correction and no VFX, or is destined for the web, then you can probably get away with lower bit-depth, chroma subsampling, and macro blocking that come with lower-quality capture codecs.

“If a production needs no, or minimal, grading and/or a quick turnaround, a camera like Canon’s XF705, with its direct HDR recording capability, would be a great choice,” suggests Paul Atkinson, pro video product specialist, Canon Europe.

“Certainly, if your production is really effects-heavy, then you should be filming in a full 4:4:4 colour space since chroma key requires super-accurate colour information,” confirms Barry Bassett, managing director at camera rental shop VMI. “If you are planning on mastering with an HDR version, then you will require recording in Log format and for this shooting Raw is ideal.”

“The benefit of working with Raw is that you’ve got full control of what can be extracted from the original file,” Francisco Lima, Gramercy Park Studios

The Raw downsides

In spite of the image-quality benefits of Raw, there are two major downsides: larger file sizes and extra processing requirements. That means more memory cards, more hard drives, and more time spent copying files. Raw video also takes significantly more processing power in order to view, edit, or transcode.

To pass them through a post workflow without incurring massive storage costs or bottleneck delays in throughput, Raw files typically need transcoding (converting) into proxies for editing before being replaced with the original footage for effects and mastering. For example, Panasonic offers a proxy compression method within AVC-Ultra which records a low-rate, high-resolution proxy video for a straightforward edit file or streaming purposes.

“Working with smaller resolution, data rate and file size will allow the editor to work faster as the transcoded files are lighter, especially in jobs where the editor is having to cut and overlay multiple videos,” says Lima.

Cave advises, “You want to try and keep the files native for as long as you can to keep as much of the original quality as possible.”

Apple and Blackmagic Raw

And that’s where the latest Raw innovations from Blackmagic Design and Apple come in. Last April Apple released a Raw version of ProRes, and last month camera maker Blackmagic announced its own version of Raw in direct competition to ProRes (though Blackmagic Design say that they began work on their Raw codec several years ago and its 2018 release with ProRes Raw is coincidental).

What’s different about both is that they’ve worked out a way of retaining all (or most) of the quality of Raw but in smaller file sizes associated with compressed formats.

Some manufacturers have already gone this route but kept it within their own product range. Sony devised X-OCN, which features in the Venice camera, to retain everything the sensor sees but at lower bit rates; a Light version of Canon Raw (available on the EOS C200) records internally to CFast cards offering a reduction in file size, while still allowing for extensive grading possibilities.

Apple claims ProRes Raw (which comes in an even higher quality HQ version) offers superior performance in both playback and rendering to codecs like Redcode Raw and Canon Cinema Raw and supported this claim with benchmarks tests, albeit only within Apple Final Cut Pro.

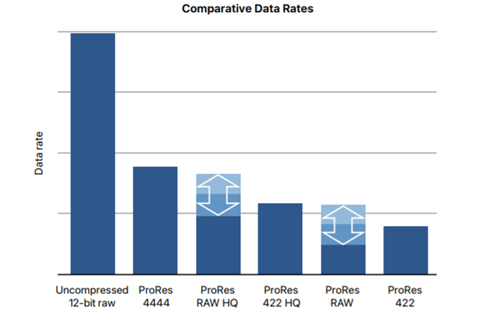

With most video codecs, including ProRes, a technique known as rate control is used to dynamically adjust compression to meet a target data rate. This means that, in practice, the amount of compression varies from frame to frame depending on the image content. In contrast, Apple designed ProRes Raw to “maintain constant quality and pristine image fidelity” for all frames. As a result, images with greater detail or sensor noise are encoded at higher data rates and produce larger file sizes. Nonetheless, it has managed to get ProRes Raw’s data rates down to less than that of its previous next best codec ProRes 4444.

“ProRes Raw does have much smaller file sizes than even ProRes 4444 so this is cheaper to shoot (less card storage); has less media to move (both for copying to hard drive and also for cloning); less data to move in post; store; less render time etc,” says Bassett.

“ProRes is not as efficient as ProRes Raw, but remains popular and reassuring when production teams do not want to take a risk with their work,” says Oliver Newland, regional marketing manager, Panasonic UK.

Blackmagic’s solution to the problem of processing power requirements is to move part of the process into the camera, which is able to provide hardware-based acceleration. By performing this in-camera, software like Blackmagic’s DaVinci Resolve won’t need to work nearly as hard to decode the files, the firm says.

There are two variable bit-rate levels of ProRes Raw being introduced. ProRes Raw HQ and ProRes Raw record at similar data rates as their ProRes counterparts as seen left.

This efficiency allows Raw data to be stored with similar memory space as common video files, meaning that you can edit and colour natively in Raw on FCPX on a MacBook Pro. ProRes Raw files will also output from FCPX to video finishing formats faster than other Raw formats.

Raw on a laptop

Both Apple and Blackmagic’s Raw innovations promise to speed the transfer of data files from camera through post but they also have the potential to eliminate the need for proxies. Raw editing on a laptop could soon become a practical reality. Working with, storing, and coming back to projects using ProRes or Blackmagic Raw should be seamless.

Kees Van Oostrum, president of the American Society of Cinematographers, even claims that Blackmagic’s tech “could entirely change the workflow going from camera through post production… because the editorial team can work with the camera original files, which are fast enough to use for everyday editing.”

A number of products already support recording of ProRes Raw including Atomos, maker of the Shogun Inferno recorder/monitor and DJI’s Zenmuse X7 camera and Inspire 2 drone. Currently, though, the codec is reserved for editing and finishing on Final Cut, isolating non-Mac OS users for the time being.

Blackmagic Design Raw, currently in beta and compatible only with its URSA Mini Pro, is - like ProRes - designed to work with third party equipment via an SDK (Apple also requires vendors pay a licence). By NAB next April you can expect more product such as recorders and NLEs to be able to decode and play files in both codecs.

Raw alternatives

These are far from the only Raw deals in town. ARRIRAW is a proprietary, uncompressed and unencrypted Raw format, which can be recorded and reviewed on the camera directly and processed with the ARRIRAW SDK.

“Because ARRIRAW is not encrypted, it is open for image processing with third party tools, such as Davinci Resolve or Colorfront OSD, which offer the ARRI processing chain as well as their own,” says Henning Raedlein, head of digital workflow solutions at ARRI.

There are also mathematically lossless schemes available for ARRI cameras, such as Codex HDE, which reduce the data footprint “with bit-identical results”.

Earlier this year, Red released an updated version of its image processing pipeline (IPP2) which is a Red-specific means of managing the RAW sensor data and notably the colorimetry to the final image output. A particular goal in IPP2 is to support HDR with new on-set HDR monitoring controls.

The new VariCam Pure meanwhile is a camera system designed by both Panasonic and Codex to capture 4K Raw at up to 120fps via Codex’s Production Suite. In turn, this delivers ProRes in addition to all other required deliverables. This system was used by Vanja Cernjul, ASC to film the feature Crazy Rich Asians.

“In future, we expect to see the entire industry moving towards codecs that offer efficiency compression, and improved codec algorithms to further reduce the codec data rates, especially with H265 technology,” Oliver Newland, Panasonic

HEVC for broadcast shooting

Panasonic has also brought out an AVC-Intra LT codec for the VariCam LT that permits recording of 4K 422 10-bit at 50p or 60p with the same bitrate as 25p or 30p. “This is a smart codec that partially compresses before the de-bayering process when the data amount is still low,” explains Newland.

The move to 4K UHD requires an even more careful balance of output versus budget for post, storage and archive. A solution to this is to use HEVC, the MPEG standard which produces files with greater compression than the current standard (H.264), but enables 4K footage to be captured at high bitrates on easily available recording media such as SD cards.

Canon is first out of the hatch with the first pro-camcorder capable of working with this codec. The XF705, launched September includes the XF-HEVC format as an option. According to Canon, it can record 4K UHD 50 frames a second at around 160Mbps as 4:2:2 10-bit files directly to SD cards. The file is wrapped for post with the widely used Material eXchange Format (MXF).

Other manufacturers are expected to follow suit. “In future, we expect to see the entire industry moving towards codecs that offer efficiency compression, and improved codec algorithms to further reduce the codec data rates, especially with H265 technology,” says Newland. “This will provide the same quality for less bit-rate than H264.”

Individual preference

Selecting one codec over another for acquisition can also depend on individual preference.

Mark Toia, a director and DP of commercials for clients like Virgin Airlines and Coca-Cola uses Red cameras almost exclusively on top end jobs. “I’ll use the 8K sensor all the time now but I’ll shoot 11:1 in Red’s compressed format unless I’m using lots of VFX for keying and green screen in which case I’ll go 3:1 or 5:1.

He doesn’t set LUTs (a colour correction preset in-camera) or worry about an under exposed shot. “All I am after is the angle and the content because I can work with the Raw and pull out any detail I want after the fact,” he says.

By contrast, director John Mathieson, BSC (X-Men: First Class, Mary Queen of Scots) dislikes the whole concept of Raw, finding that the images tend to be “confused, washed out and looking indistinguishable from any other film.” He urges film school graduates to be taught how to light and expose a picture using 16mm as the basis for successfully working in digital.

Ultimately, choice of compression needs weighting the proposed resolution, frame rate and visual preferences versus time constraints and budget.

Choice can even come down to something as unscientific as the most powerful personality among the crew - “DITs with an inflated sense of their own importance,” observes Bassett, “who insist that a specific codec is crucial.”

Read more Codec wars: The battle between HEVC and AV1

Read more HEVC, AV1, VVC and XVC: The codec battle intensifies

No comments yet