BBC Research and Development has published a white paper, Object-Based Media - An Overview Of The User Experience, to coincide with IBC2020. Ann-Marie Corvin presents a summary of the study, followed by an exclusive Q&A with the paper’s lead author, Maxine Glancy, senior research scientist at BBC R&D.

Object-Based Media (OBM) is a developing format that allows a piece of content to change according to the requirements of individual consumers. One example would be a TV show which, at certain points along the way, allows each viewer to drill down deeper into segments of the show, or to skip over the detail and opt for the briefer version. These experiences can also be audio-based or can play around with elements of audio, video and text. More complex versions involve putting users at the centre of the narrative or can involve multiple users.

Maxine Glancy: ‘we move from the idea of the audience as a largely passive consumer of the media, to becoming the active protagonist’

In its analysis of the OBM user experience (UX), the paper evaluates a number of use cases which fall into three different categories.

Case 1: Adapting the narrative

The simplest form of OBM the paper identifies are programmes where users get to make choices about the flow of narrative. One of these ‘branching narrative’ shows includes the 1000th episode of the BBC technology series Click, which developed an interactive factual programme that allowed viewers to choose from many alternative versions. Based on choices explained by the shows’ presenter, users could choose the level of the explanation they required for each segment of the show. The experiences of those watching Click1000 through the BBC’s experimental Taster website were subsequently analysed by BBC R&D.

The paper found that the simple dialogue between the audience and the presenters resulted in a high level of engagement with the story. However, there appears to be room for improvement as some users felt that offering multiple layers of information resulted in a show that was just too long. Other users reported feeling lost as to where they were in the show’s overall narrative and wondered whether they had missed out on important details.

- Read more: Immerse: A platform for production, delivery and orchestration of distributed media applications

Case 2: Layered experiences

The second type of OBM identified were ‘layered’ shows that enable users to adapt the AV presentation of the narrative. Content here usually takes the form of a linear show but gives viewers control over what media is audible or visible along the narrative path. It can also allow them to choose the relative mix of the media components.

Increasing access to programming through personalisation of content is a key example of the use-case. The paper looks at how the drama series Casualty achieved this for audiences with hearing needs in the Accessible and Enhanced (A&E) Audio project.

The episode, published on BBC’s Taster website, allowed viewers to personalise the audio of an episode with an easy-to-use single slider. This could be varied between the broadcast mix and an accessible mix containing narratively important non-speech sounds, enhanced dialogue, and attenuated background sounds.

User activity data and feedback from an online questionnaire highlighted the benefits that this episode presented to deaf and hard-of-hearing users. Over six thousand viewers tried it and 84 per cent reported that it made a difference. Specifically, almost three quarters of respondents added that it made the content more enjoyable, or easier to understand.

Maxine Glancy: ‘OBM approaches add value by utilising the wealth of assets like different camera angles, audio feeds and statistics to augment the viewer experience’

One respondent (from an early stage trial) told researchers: This kind of audio personalisation “puts us back in control. We are in charge of what we hear, and I think that’s quite empowering.”

The paper found that adapting presentation of the narrative was also used effectively in live events, particularly through the EU-funded 2-Immerse project, including the MotoGP at Home, Football at Home and Football Fanzone experiences – which were demonstrated in the Future Zone at IBC2018. All of these projects were built to accompany a live sports event, providing users with personalised coverage that could be controlled to suit their level of interest.

Case 3: User takes centre stage

The third type of OBM experience the report identifies allows the user to move through the narrative at their own pace, adding to or adapting the content of the narrative. The user essentially takes the role of the protagonist and requires all the information they might need up front, with nothing hidden or obscured.

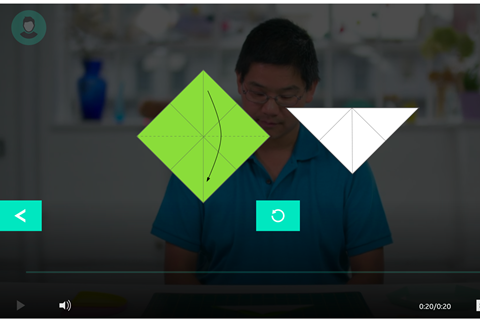

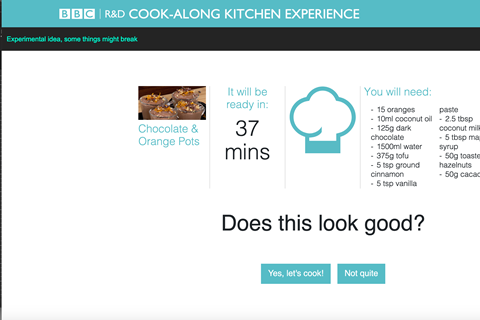

The OBMs Make-along and Cook-Along Kitchen Experience (CAKE ) are good examples of this form.

Make-along, which ran alongside the BBC TV show, MAKE! Craft Britain, offered a special interactive origami tutorial, giving viewers the ability to change the camera angle, repeat steps in the lesson and take the exercise at a pace that suits them. CAKE, an IP-delivered OBM interactive cookery experience, was an earlier protype. Through data analytics and user feedback from the BBC Taster platform, users spoke about feeling ‘in creative control’ and of being ‘part of the experience’, as though the tutor was talking directly to them rather than being disconnected on a screen.

Users also reported that the segmented, real-time nature of the experiences helped users by matching the instructions to their current task, and the facilitated coordination of tasks made them feel better supported than in other learning/tutorial processes.

It’s clear that this form of OBM may play an important role in supporting self-learning among students. A more complex example of this form which the paper goes into greater detail about is Theatre in Schools, which involves multiple users and a teacher/ curator.

Object-Based Media - An Overview Of The User Experience, by Maxine Glancy, Lauren Ward, Nick Hanson, Andy Brown and Michael Armstrong [September 2020], can be read in full at the BBC R&D site

Q&A

IBC365 interviewed Maxine Glancy, senior research scientist at BBC R&D, about some of the paper’s key findings.

Q: Is OBM a complementary media to existing TV shows - or a new form of entertainment in its own right?

A: The Casualty and Click 1000 examples are brand extensions, whereas CAKE and Make-Along arguably represent a new form. In [the latter form] we move from the idea of the audience as a largely passive consumer of the media, to becoming the active protagonist making the meal or folding paper (a more Brechtian experience, in theatre parlance). However, all OBM experiences make alterations to the UX and with that come new challenges.

Q: Is this why you conclude that a training section is advisable, in the early part of the experience?

A: One of the key elements that contribute to success for new forms of media or new forms of interaction is the provision of a training section, where the user can gain familiarity with the controls without missing important parts of the experience. One of the main observations with customisable media is that, on the whole, the user will begin by trying out the controls until they settle on a set-up that fits their needs.

Q: What do you think the main use cases for OBM will be?

A: This depends largely on the type of OBM approach used. Variable length and branching content are particularly suited to use in factual, magazine style content as well as news. These content types are naturally segmented, so lend themselves to allowing viewers to drill down into a particular topic based on their interests and time available.

A lot of the work we’re looking at going forward is around live events and sports and supporting these genres. Here OBM approaches add value by utilising the wealth of assets like different camera angles, audio feeds and statistics to augment the viewer experience.

Another key use case is improving the accessibility of content through the ability to personalise the audio, or other aspects of the content. This is most applicable to dramatic content, where mixes are more complex and production times are longer. Furthermore, as these approaches tend to involve adding metadata to existing assets, rather than generating new assets, this also presents a lower barrier to uptake than many other use cases.

Q: One of the UX challenges associated with OBM – particularly the branching narrative examples – is that ‘fear of missing out’. That is, viewers have to make explicit choices, yet are still curious about the ones they’ve rejected.

A: One of the conclusions we come to in the paper is that some kind of visual mapping within the user interface (UI) is needed to guide the viewer and help them keep track of what they’ve consumed and where they have gone so far. I also think that giving users particular functions and capabilities – to be able to go back and do it again, for example, with a guarantee of experiencing something new, will address that FOMO. There are different ways you can do this within the UI – a map or an alert summary, for example, to make sure they don’t feel that anxiety.

Q: Viewers seem to be split into active engagers who like having choices available to them throughout the experience, and those who prefer to make certain choices upfront and then not be distracted. How do you cater for both?

A: Asking explicit questions up front can help tailor the content for different user preferences, as well as having OBM driven by personal data, the time of day, or past preferences and so on. In the long term, automating personalisation could be the answer. With the aid of saved user data and more sophisticated experience designs, a viewer might be able to watch a natural history experience and have it automatically provide them with content that is tailored to their interests and level of knowledge.

Q: How long is a typical OBM experience?

A: Some of the live experiences are defined by the events themselves, and with Make-along it depends how quickly you’re able to perform the task. In the case of Click 1000, it was based on a programme of a dedicated length, but if you went off and looked at all the extra detail of everything, that made it longer.

Q: Some Click 1000 users reported that the extra layers of information resulted in a show that was too long. What can UX designers do to mitigate this?

A: The answer is to build shorter experiences. Or you enable people to consume the experience as a series of episodes, and keep track of where they are and what they have done so far.

Twitter feedback for Click1000 revealed that the main audience concerns were less about the length and more about the inability to track what you had and hadn’t seen – some suggested a map or index – and the fact that you had to start back at the beginning each time and repeat the opening to fully explore the available content.

Q. What production tools are people using to create the OBM UX?

A: We use StoryFormer – a BBC R&D OBM web-based tool used for creating responsive stories. The OBM Tools are publicly available on the BBC Taster Website, and we’re exploring how such tools could be part of future production processes.

Read more Object-Based Media: An Overview Of The User Experience

No comments yet