Ophélie Boucaud, Principal Analyst at Dataxis, sheds some light on the quest for more relevant and comparable performance metrics in the ad-supported streaming world, and what needs to happen to create greater transparency.

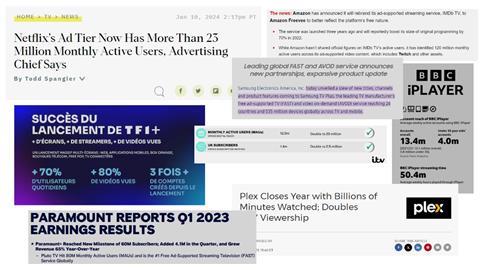

Assessing the performances of ad-supported free streaming services has become a game of comparing apples and bananas in recent years. The ad-supported video-on-demand (AVOD) and free ad-supported TV (FAST) industries are notoriously hard to evaluate because each actor will use their own methodology and proprietary KPIs when issuing information on their uptake. Some platforms will share their reach, others will talk about engagement and usage, competitors will push high registration numbers, and only a handful of them share their volume metrics in terms of viewing time.

The infamous Monthly Active Users (MAU) KPI is also highly contested, mostly because the calculation methodology highly differs from one service to another. And that’s before we even get onto the streamers that do away with this somewhat industry-wide accepted metric and instead disclose volume KPIs as unique users per year, weekly active users, or even a 90-day active base, among others.

Why are OTT platforms so reluctant to share MAUs?

Not every platform is keen to share metrics on active users. CTV platforms for example are only half-heartedly publishing the largest and least relevant metric they have in store, i.e. the total number of devices equipped with their ad-supported apps. In the case of Samsung’s TV Plus FAST platform, for example, it reached 535 million devices with its service last November, but this just tells us that the app has been placed on its devices. Nothing was shared since 2021 about the active user base or the total viewing time spent on the app. But clearly, this huge number resonates with advertisers and is much more impressive.

Read more: FOX, Warner Bros. Discovery and ESPN launch sports streaming giant

Other notorious FAST platforms also don’t give us much to work with. Platforms like Plex or Rakuten Free only occasionally drop a few figures. Amazon’s communication on Freevee is extremely limited, and the last shared figures account for the overall active user base of ad-supported platforms supported by the group, including Twitch. Viacom-backed Pluto TV was historically more generous, sharing its quarterly MAU in the USA up to the end of 2020 and globally up to Q1 2023. This isn’t the case anymore, and one may wonder if this change in reporting is a reflection of slowing growth or an overall weariness of being among the only few providing more transparency.

When looking at broadcaster video-on-demand (BVOD) platforms, we enter a whole other realm of KPIs. In Europe, the largest British services like ITVX and All4 are sharing MAU, registered users, and the volume of viewing time regularly; which makes it rather easy to identify the best performing among them and better evaluate how this evolves over time. But this is only partly true, since BBC iPlayer is sharing weekly active users instead of MAU, and Channel 5 has never disclosed much of my5’s active user base.

The last service to date to launch in Western Europe is TF1+, the rebranded and bulked-up OTT service of the largest French commercial broadcaster TF1 Group. The communication after launch revolved around other significant metrics to highlight its performance: uptake in daily active users, number of videos watched, and the increase in the number of registrations. Of course, it’s a bit early to talk about monthly active users when the service has been online for a short time, but those KPIs, especially the ones around how people interact and consume content on the platform, might be a better way to look at ad-supported platforms, rather than the infamous MAU metric.

Why we should look less at MAUs and more at, well, everything else

Why are OTT platforms weary of sharing their MAUs? Well, one big reason is that it’s not the most flattering metric. A free service’s user base is generally way more volatile than a paying subscriber base, since paying users are billed every month and active usage isn’t something that subscription video-on-demand (SVOD) services have to even communicate on. That explains why OTT services are less likely to share this KPI regularly: their active base may vary significantly from one period to the next, which would worry or even unnerve investors.

Churn matters much less for ad-supported streaming services, since they don’t need to rack up huge subscriber acquisition campaigns, unlike their paying counterparts. But active user base is an unforgiving metric that specifically reflects high levels of churn, and it’s a bad one to share for this reason. It also doesn’t tell us anything about how engaged people are with the platform, how much time they spend on it, and most importantly, how effective advertising is on conversion - which is ultimately what brands and investors are interested in.

A second big point: the active user base of OTT platforms is still way off when compared to the reach of linear channels. Using the example of ITVX, which is the most performing BVOD service in Europe right now, its platform reached around 12.5 million active users each month in mid-2023, but the UK’s broadcast channels reach 83% of the population every week or around 55 million people.

Read more: EBU launches Eurovision Sport streaming platform

The overall lack of transparency and relevant industry currencies to assess the value and performance of ad-supported services has resulted in some regretful situations. At the end of 2022, right after Netflix rolled out its new advertising tier, it was almost immediately shunned by advertisers who wanted their money back as the streamer couldn’t deliver on the views and impressions it was aiming for. Of course, it was normal that a premium video service that consistently claimed to have never dipped its toes in advertising for a decade would have a hard time making volumes in the first quarters of the ad-tier launch. However, greater transparency would likely have helped to soothe unhappy clients. It would probably also help Netflix scale the business further (we are still at the point of making educated guesses when it comes to mapping where the 23 million Netflix ad-tier users are based).

What needs to be done?

On the linear side, metrics have been crafted over years of measurement on broadcast TV, and by (mostly) neutral observing bodies who don’t run the PR for one specific media house when reporting figures. The likes of Nielsen and Kantar, but also local bodies like BARB, Médiamétrie, AGF, or Auditel, have established themselves as truth-tellers when it comes to understanding the TV landscape in their respective operating markets.

However, not all of them have yet taken the same fundamental role when it comes to measuring OTT and digital media. Measurement currencies on these segments are also highly fragmented from one territory to another, which doesn’t help observers come up with a satisfying methodology for global comparisons.

Right now, anyone and everyone can suggest their own KPIs and calculations for performance. That’s not necessarily a bad thing since the alternative would be one giant media house (Google?) telling us what should count as a user or a view. But too much fragmentation is not good either, since it means that we are juggling with irrelevant figures when put next to one another. And that’s an unreasonable and very opaque way to structure the publishers’ markets.

Advertisers have never had access to more precise metrics on the big screen since the inception of CTV advertising. But this is confined to the framework of their campaigns, and the CTV advertising industry overall has been quite shy in making data publicly available. So how are advertisers supposed to understand the overall landscape in which they’re putting their budget? How are we supposed to assess the performance and relevance of streaming services in the ad-tier era? How can we learn how to better address viewers’ needs when we can’t have a clear view of the consumer market?

A few ideas that many are already working on and that are yet to take a bigger part in the industry debate include:

- Start reporting on engagement with the content. Streamers need to give us more metrics on their IPs’ performance and the popularity of content. The industry is getting there slowly as it is virtually transparent on YouTube and other social media, and it’s also the direction taken by Netflix with its publications on viewing time per title.

- Get the people who have access to this information to be a gateway to those metrics. Ad-techs are very well positioned to understand the industry they navigate in and have privileged access to their client’s KPIs, but opening up those floodgates requires some serious and deep talks about the data walled gardens issues.

- Commission neutral measurement bodies to step up their game on digital and push publishers to work alongside them to set up industry currencies that are comparable from one platform to another, and (dare we dream of it) from one market to another.

This will all result in way more transparency. Digital streaming services don’t seem ready for it yet, but once they achieve critical mass it will be the next natural next step for them. Just look at Netflix which had to start working with measurement bodies in 2022 to guarantee reliable third-party metrics for campaign measurement. It would mean letting go of the walled gardens’ privilege, but enabling the whole industry to become more accessible to media buyers. And seeing how all streamers are slowly putting their eggs in the ad basket for the foreseeable future, it’s a necessary step for 2024.

Read more: ISE 2024: In what ways are big brands and corporations becoming the new broadcasters?

No comments yet